The UN climate talks were held in the heart of the Amazon for the first time, taking place 10–21 November 2025. Located in Belém, COP30 catalyzed global attention to the intersections of climate, forests, and food systems. With governments, multilateral institutions, researchers, and civil society gathered in one of the world’s most climate-vulnerable regions, expectations for meaningful progress were high.

To understand what COP30 delivered and where it fell short, The Foodscapes Collective spoke with four groups of experts and practitioners working at the frontlines of climate, forest, and food systems. Their reflections reveal a conference marked by moments of real progress alongside familiar shortcomings. The themes that follow reflect what stood out most in these conversations, highlighting what worked, what fell short, and what comes next.

What Worked

Despite significant challenges, several meaningful achievements were identified.

1. Food systems gained global visibility

This year marked a clear shift in how food systems are positioned within global climate discussions. While agriculture and food have historically been treated at COPs as secondary thoughts or distant and highly technical issues, Belém represented a moment where food systems were widely recognized as central to the conversation.

“COP30 made it clear that climate change, food security and poverty are parts of the same public-policy challenge,” says Analía Luisa Stasi, Senior Advisor for Public Sector Governance and Multilateral Cooperation at the Inter-American Development Bank. “There was increasing recognition that transforming agrifood systems is essential, not only for adaptation, but also for economic and social stability.”

Multiple interviewees pointed to the Global Climate Action Agenda, particularly its priority on Transforming Food Systems and Agriculture, as an important positive takeaway from this year’s conference.

“The COP30 Presidency elevated food and agriculture as one of six pillars in the COP30 Action Agenda, a voluntary set of initiatives designed to accelerate implementation. These voluntary initiatives can help set practical direction, unlock investment, and lay the groundwork for climate action,” says Rachel Juel, Public Health PhD student at Istituto Superiore di Sanità-Sapienza, specializing in climate change, food systems, and health.

Laura Jessie Cook, Director of Communications at ALLFED and Senior Strategist with Project Dandelion adds, “the Action Agenda revealed the power of real-world implementation for building resilience in our systems. It ran alongside the COP in a way that showed something vital: communities, cities, businesses, and sub-national leaders are already acting, already adapting, already building the foundations of resilience.”

2. Forests and land use gained historic momentum

The launch of the Tropical Forest Forever Facility (TFFF), backed by over USD 5.5 billion and endorsed by 53 countries, marked a major advance in forest finance.

Juel noted that the facility, “demonstrated a growing willingness to channel significant resources toward keeping forests standing and supporting sustainable land-use transitions.”

The TFFF marks a major shift in global forest protection by valuing and paying for the ecosystem services of tropical forests. It creates a new, large-scale financial incentive to keep forests standing rather than clearing them.

Beyond the scale of financing, the TFFF also reflects a shift in how tropical forests are framed within global climate governance with the inclusion of the Amazonian perspective. Prof. Dr. José Sobreiro Filho and Emilly Firmino Oliveira de Lima, Institute of Human Sciences, Department of Geography, University of Brasília describe it as an advance in “facilitating the world’s understanding of the impacts and challenges orbiting climate change in the Global South and in the context of tropical forests.”

While its long-term impact will depend on implementation, governance, and equity, the launch of the TFFF at COP30 signaled something critical: protecting tropical forests is no longer treated solely as an environmental imperative. It is increasingly being recognized as a core pillar of global climate and development finance.

3. Global cooperation held together in a difficult year

The Brazilian Presidency of COP30 played a stabilizing role that many observers viewed as essential. While COP30 did not deliver all the ambition many had hoped for, it avoided a far more damaging outcome: the collapse of negotiations altogether. Previous COPs have shown how quickly talks can unravel under political pressure and, in some cases, even lead to walkouts.

Cook described the Brazilian Presidency’s ability to prevent a collapse of the talks as “an achievement of sorts.” Despite a fire at the venue, fraught geopolitics, protests, and “a chaotic final 24 hours,” the COP30 presidency managed to “keep countries in the room and keep negotiations alive.”

The achievement was especially significant in a year when global cooperation was fracturing and top U.S. officials were absent from the talks. As Cook put it, “In a year when global cooperation has been very weak, this was an important achievement.”

4. COP30 sparked conversations and mobilization beyond the official event

One of the most powerful outcomes of COP30 unfolded outside the negotiation halls. The conference served as a catalyst for regional mobilization, political debate, and community-led gatherings across the Amazon.

Sobreiro Filho and Oliveira de Lima described this dynamic, saying, “COP30 was a vast mix of relationships of different natures, especially because it was far more complex than the event’s own schedule could explain. It was preceded and surrounded by dozens of other events organized by grassroots peasant, Indigenous, traditional, and workers’ movements.”

In the months leading up to COP30, these popular movements organized preparatory assemblies, regional meetings, and political dialogues across Amazonian territories. During the conference itself, this mobilization intensified. Dozens of organizations from rural areas, forests, rivers, and urban peripheries convened parallel events throughout Belém.

Indigenous participation, in particular, reached historic levels. COP30 saw more than 900 Indigenous participants, nearly triple the number from the previous year. Indigenous leaders used both formal and informal platforms to advance proposals on territorial governance, forest stewardship, and climate adaptation grounded in lived experience.

COP30 also spurred political outcomes beyond the 12 days of conferences. On 7 November 2025, ahead of the official program, leaders from 43 countries adopted the Belém Declaration on Hunger, Poverty, and Human-Centered Climate Action, linking climate action with food access, inequality, and social protection.

What Fell Short

Despite these advances, the experts also pointed to significant shortcomings.

1. No progress on fossil fuels or deforestation

Perhaps the most consequential, and widely reported, failure of COP30 was the lack of progress on fossil fuels language. For many observers, this became the defining headline of the conference. Despite the powerful symbolism of hosting a COP in the Amazon, countries failed to agree on a fossil fuel phase-out, a transition roadmap, or even including direct reference to the fossil fuels that are heating up the planet.

Laura Cook described this outcome bluntly:

“The negotiated text was weak on fossil fuels and deforestation. Despite over 80 countries supporting a fossil fuel phase-out and the Amazon being the host region, COP30 delivered no fossil fuel roadmap, no phase-out language, and no deforestation roadmap. These gaps were seen by many as serious failures, especially given the urgency and the symbolism of Belém.”

The disconnect between context and outcome was striking. Holding COP30 in the Amazon raised expectations that forest protection and fossil fuel reduction would be central pillars of the formal negotiations. Instead, the final texts reflected lowest-common-denominator politics, where resistance from a small number of countries was enough to block progress on the most urgent drivers of the climate crisis.

Sobreiro Filho and Oliveira de Lima framed this failure in moral and political terms, emphasizing its global consequences:

“This can be seen because the countries responsible for CO₂ emissions continue without effectively committing to their respective responsibilities, maintaining relative and timid commitments. This means there is still a profound disregard for the lives and heritage of many impoverished populations in the world.”

Their critique underscores how the absence of strong commitments on fossil fuels is not a technical oversight. Rather, it reflects entrenched power imbalances within the COP process. Those most responsible for emissions continue to delay decisive action, while frontline communities, particularly in forest regions like the Amazon, bear the costs.

2. Lack of progress in the formal negotiations on food systems

Despite the strong visibility of food systems throughout COP30, the formal negotiations failed to deliver actual progress. While food and agriculture featured prominently in panels, pavilions, and high-level initiatives, the official outcome text did not advance binding commitments on agricultural emissions, adaptation, or implementation support.

Juel noted the paradox, saying, “in the formal negotiating spaces, food systems were still too contentious for countries to make meaningful, binding commitments. Yet everywhere outside those rooms—on panels, in pavilions, and in high-level initiatives—food systems were upheld as central to solving the climate crisis.” She described this as “the biggest missed opportunity,” pointing to a disconnect between political recognition and political action.

This gap is evident in the final Mutirão Decision. The document contains no direct mention of food systems, despite their prominence throughout the conference. Food is only mentioned indirectly when referencing Article 2 of the Paris Agreement, which reads: “Increasing the ability to adapt to the adverse impacts of climate change and foster climate resilience and low greenhouse gas emissions development, in a manner that does not threaten food production.”

It is notable that the word “food” appears only three times in the entire Paris Agreement. Food security and food production are largely framed as vulnerabilities to climate change, rather than as sectors that also contribute significantly to global emissions. As a result, there is no language that directly acknowledges the role of agro-food systems in driving climate change, mirroring the broader reluctance to explicitly address the role of fossil fuels.

Stasi reinforced this concern on the lack of progress, noting a “lack of a clear strategy for directing financing toward agrifood systems, despite their importance for adaptation and economic stability.”

Despite strong data presented by international institutions, these issues were largely treated in isolation, and no formal negotiated strategy emerged for directing finance toward agrifood systems, even though their role in adaptation and economic stability is widely recognized.

3. Indigenous knowledge was acknowledged but not embedded

While Indigenous knowledge and traditional practices were frequently acknowledged at COP30, they were rarely embedded into concrete policy tools. Traditional approaches were discussed, but they were not translated into the formal negotiations.

“COP30 did not enable popular participation,” says Sobreiro Filho and Oliveria de Lima. “COP30 failed in its proposal of democratization and participation. It was not popular and accessible; it followed the same models that create a segregated COP.”

Process integrity and inclusion were also major shortcomings. The COP was inaccessible for many Global South and frontline communities. Fossil fuel lobbyists were heavily present and many participants felt the process was captured by powerful interests.

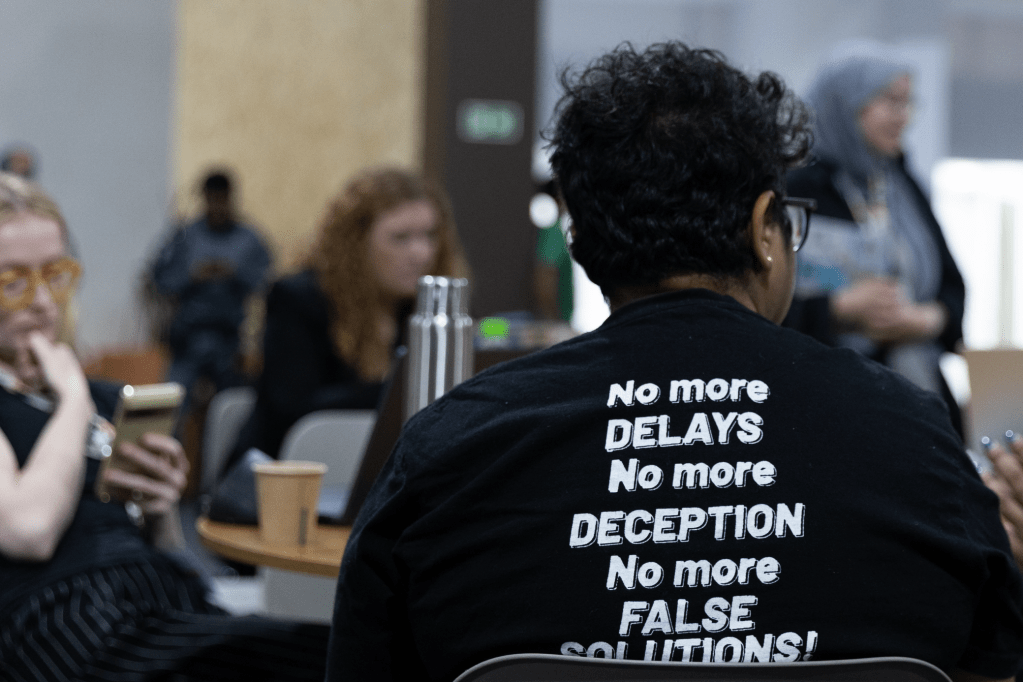

Cook explains, “The COP process became exclusionary and structurally unfair. COP30 was extremely expensive for many Global South and frontline communities, shutting people out. Those who did attend often faced militarised responses to protest, were excluded from key negotiations, and watched more than 1,600 fossil fuel lobbyists gain access. This created a feeling of a process captured by powerful interests and inaccessible to those most affected by the crisis.”

Stasi summarizes this by saying, “while Indigenous practices were mentioned, their incorporation into public-policy instruments—such as territorial planning, extension services or early-warning systems—remains limited.”

What Comes Next

While their perspectives differed, the experts shared a belief that the future of climate action depends on how lessons from COP30 are carried forward and translated into action.

For Laura Jessie Cook, the central challenge is not whether COPs should continue, but whether they can evolve to meet the scale of the crisis. She argues that multilateralism still matters, even as the COP process shows signs of strain. As she reflected, “we still need COPs, multilateralism matters, and there were real moments of hope in Belém. But the process, as it currently exists, is starting to consume itself. Too often the machinery of COP feels more focused on sustaining its own procedures and performance than on actually responding to the urgency of the planetary crisis.”

Rather than abandoning the process, Cook calls for transformation. “I don’t want COPs to end; I want them to transform — to shape-shift into something more human, just, accountable, and fit for the world they’re meant to serve,” she said. At the same time, she emphasized that progress cannot rely on negotiations alone. “Policy matters, planning matters, but so does determined, practical effort from every part of society.”

Read more from Laura Jessie Cook over at her Substack.

Rachel Juel sees growing momentum for food systems, but stresses that visibility must now translate into binding action. She believes it is inevitable that food systems will enter the formal negotiating space, noting, “It’s only a matter of time (and some serious political will) that food systems makes its way into the legally binding texts.”

For Juel, turning COP30’s voluntary commitments into meaningful outcomes requires several concrete shifts. “To turn COP30’s voluntary commitments on food and agriculture into meaningful action, three things need to happen next,” she explained.

First, “Countries must integrate food systems into their national climate plans. This includes mitigation strategies, adaptation plans, and investment frameworks that reflect the central role of land-use change, agriculture, and food security in meeting climate targets.”

Second, “Climate finance needs to shift toward food system transformation.” She pointed out that “Currently, only about 4% of climate finance goes to agrifood systems despite the sector contributing roughly one-third of global emissions and facing enormous adaptation needs. More targeted and sustained investment is essential.”

Third, “Implementation must be strengthened through measurable, equitable, and locally grounded pathways.”

This, Juel emphasized, requires real investment on the ground. “This means investing in rural livelihoods, climate-resilient agriculture, regenerative land management, and knowledge and capacity-building systems that allow communities to adapt and thrive.” If these shifts occur, she believes the momentum from Belém could have lasting impact. “If these shifts occur, the momentum generated in Belém could translate into a real turning point—one where food systems move from voluntary commitments to being core pillars of legally binding climate action.”

For Analía Luisa Stasi, the path forward lies in stronger governance and deeper regional cooperation. She emphasized the importance of integrating climate risk, food access, and inequality into cohesive national strategies, noting the value of Indigenous practices, including “diversified cropping and community-based land stewardship.”

Stasi expressed cautious optimism about the direction of policy discussions. “There is room for optimism in the way scientific evidence, poverty diagnostics and technological innovation are beginning to intersect with governance discussions,” she said. However, she stressed that ambition must be reflected in concrete national decisions. “Countries will need to reflect their climate commitments in national plans, budgets and food-system policies. Cooperation between the EU and LAC will be essential, as both regions can advance shared standards, financing models and institutional-capacity efforts. Moving toward 2030 will require treating climate risk, food access and structural poverty as components of a single governance challenge.”

In contrast, Dr. José Sobreiro Filho and Emilly Firmino Oliveira de Lima are more skeptical that meaningful transformation will emerge from multilateral negotiations alone. They argue that real change will be driven by popular movements and grassroots organizing, rather than COP outcomes. As they stated, “hope does not lie with COP30, but with the people who tirelessly continue to contest all conferences.”

For them, the priority is democratization and accountability. “It is necessary to create mechanisms for real implementation and the democratization of control and oversight forms,” they said. “It is essential to rebuild relationships with grassroots organizations and adopt an agenda with popular involvement. This must occur through the decentralized structuring of consultation and participation methods.” At the same time, they stressed that research, despite growing political pressure worldwide, was “reaffirmed as relevant for substantiating decision-making.”

Read more about the 5th National Agrarian Reform Fair: Brazilian Landless Rural Workers’ Movement written by Dr. José Sobreiro Filho and Emilly Firmino Oliveira de Lima.

Want more content like this? Subscribe to The Foodscapes Collective to be the first to know about articles like this and more.

Leave a comment